How the Civil Rights March on Washington Embodied Key Public Health Tenets

January 11, 2024 | Melissa Lewis

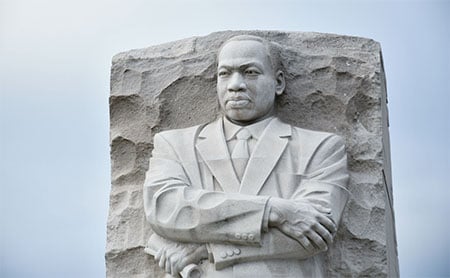

Every year on the third Monday of January, we celebrate Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr’s birthday as a federal holiday and recognize his life, legacy, and contributions as one of the most prominent civil rights leaders and activists of our generation and nation’s history. It is the only federal holiday that has also been designated as a National Day of Service to encourage Americans to take action and continue to uplift Dr. King’s legacy of social justice and equity by volunteering to improve their communities.

Every year on the third Monday of January, we celebrate Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr’s birthday as a federal holiday and recognize his life, legacy, and contributions as one of the most prominent civil rights leaders and activists of our generation and nation’s history. It is the only federal holiday that has also been designated as a National Day of Service to encourage Americans to take action and continue to uplift Dr. King’s legacy of social justice and equity by volunteering to improve their communities.

I remember learning about tolerance, equality, and citizenship in school when discussing the March on Washington and hearing snippets of Dr. King’s fiery “I have a Dream Speech.” The message galvanized the civil rights movement and the nation. And it wasn’t just the largest civil rights demonstration on record at the time; it was a powerful example of civil disobedience and sent a message of hope for a dream deferred for Black Americans and a bold stand against injustices.

On Aug. 28, 1963, more than 250,000 Americans attended the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (“the March"). And while it is one of the most celebrated speeches in our history, there are key elements of that day that were overshadowed but are still relevant today and serve as a call to action for public health professionals to reflect on as we continue to honor Dr. King’s legacy and serve our communities.

Learn from the Past to Inform the Future

The success of the March highlights the value of learning from the past and acknowledging history as an essential step to addressing equity. The original concept of the March on Washington came from A. Phillip Randolph, a labor leader and civil rights activist who planned previous marches on the nation’s capital in the 1940s to pressure the White House to address discrimination in the military. To avoid these large-scale marches, President Roosevelt passed an executive order prohibiting discrimination in the defense industry, and President Truman desegregated the U.S. Armed Forces. Although these marches were cancelled, the threat of well-organized demonstrations highlights their importance as a tool for change that informed planning for the March.

Similarly, the critical timing of the 1963 march was strategically determined to help advocate for the passage of the Civil Rights Act. During the speech, Dr. King reminded Americans about “the fierce urgency of now.“ It was the 100th anniversary of the abolishment of slavery and Black Americans were still unable to realize the American dream; they were still being oppressed, terrorized and experiencing structural discrimination. As we work to embed equity into our daily operating practices, this reminds us that moving beyond rhetoric and taking action are critical to transformational change.

Take Collective Action and Form Collaborations/Coalitions for Changemaking

The March is an example of the impact of successful collective action. The leaders of the major civil rights organizations worked together to organize the march. Dr. King and Mr. Randolph aligned their interests to plan the March. Other influential multi-racial coalitions and organizations participated, which underscores the importance of engaging communities; they organized, supported, and advocated for the March and the stalled Civil Rights legislation.

Health professionals from the Medical Committee for Civil Rights—a group sponsored by major national membership associations for doctors, nurses, dentists, and social workers—protested for change and justice to address the conditions that impact poor health outcomes. The March on Washington mirrors the marches that took place across the country to protest the murder of George Floyd in 2020. It’s a reminder to the public health field of our social justice roots and that we are also members of the communities that we seek to improve.

Value Inclusion and Center Intersectionality

Bayard Rustin, a brilliant strategist and organizer, was the chief architect of the March and an openly gay man. He faced criminalization and public attacks from opponents and members within the major civil rights organizations. This did not deter Dr. King's appreciation for Rustin’s work, nor his ability to be successful. Due to his sexual orientation, Rustin’s principal role in the march has been nearly erased from history.

The role of women in the planning and execution of the March was also paramount to its success. However, women were not given leadership roles, or the opportunity to have prominent speaking roles by meeting organizers. Some of the prominent women who contributed to the planning of the March on Washington were Dorothy Height, a civil rights activist known as the “Godmother of the Movement” and President of the National Council of Negro Women, and Anna Arnold Hedgeman, a civil rights activist and politician who was the only woman on the planning committee. Both Mr. Rustin and the women faced double oppression, but their significant impact on the March and the movement emphasizes the importance of diversity and inclusion.

As public health professionals, we must recognize that communities and individuals have multiple intersecting and overlapping identities and apply those considerations when developing and implementing interventions.

Address the Social Determinants to Advance Health Equity

Most importantly, the March on Washington underscores the importance of expanding our understanding of what creates health and addressing the community conditions—the social determinants of health (SDOH) that impact health outcomes. The March’s focus was not limited to racial equality but extended to economic justice and other social issues. More than 60 years ago, Dr. King and other leaders sounded the alarm on addressing the differences in the SDOH to achieve optimal health for all and create thriving communities. Speakers presented a list of 10 demands addressing the need for a living wage, desegregation, voting rights, employment protections, adequate housing and education, and workforce job placement and training.

Public health leaders continue to carry the torch the speakers from the March on Washington lit over 60 years ago. Their persistence to uphold health equity as a primary public health initiative may be considered an act of civil disobedience, but if the consequence is improving health for all Americans, isn’t it worth the risk?