Using Your Braiding and Layering Funding to Address Food Insecurity

August 17, 2022 | Shelby Rowell

Food insecurity is a pervasive barrier to the health and well-being of many differing vulnerable populations in the United States. According to USDA, more than 38 million people, including 12 million children, in the United States are food insecure. While food insecurity impacts most communities across the country, there are notable nuances in how it affects specific populations. Rural Americans, African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans all face increased prevalence of food insecurity within their communities.

Food insecurity is a pervasive barrier to the health and well-being of many differing vulnerable populations in the United States. According to USDA, more than 38 million people, including 12 million children, in the United States are food insecure. While food insecurity impacts most communities across the country, there are notable nuances in how it affects specific populations. Rural Americans, African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans all face increased prevalence of food insecurity within their communities.

America’s rural communities have higher rates of food insecurity than their urban counterparts. Those in rural communities are more likely to be far away from grocery stores and/or food banks, lack transportation to visit their nearest food source, are more likely to face low-wage job opportunities, and have increased levels of un-and under-employment. These barriers and inequities are even more pronounced for people of color living in rural communities. The economic hardships felt in rural communities exasperated and intensified hunger in the heartland over the course of the pandemic.

Food insecurity across minority populations is disproportionately higher due to systemic racial inequities. Within African American communities, an estimated 24% experienced hunger in 2020, with Black children being nearly three times more likely to live with food insecurity than their White counterparts. Within Latino communities, racial disparities drive hunger with the number of those experiencing food insecurity rising over 3% from 2019 to 2020. COVID-19 has also had a profound impact on the Latino community and workforce in particular, due to the massive devastation of the service sector industries through widespread layoffs.

Native Americans face high rates of poverty and food insecurity within their communities. For many in Native communities, access to food is much more difficult than in many other communities in the country. Per USDA, only 26% of those living in Native communities live within one mile from a grocery store as compared to 59% of all U.S. residents. Given the lack of access to grocery stores and supermarkets, traditional interventions such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) do not provide the same impact and benefit for Native communities.

Across communities facing food insecurity, there are unique complexities and challenges that need targeted interventions. Within this toolbox of interventions, S/THOs can implement braiding and layering funding as a strategy to consider when addressing food insecurity. Under this collaborative model, stakeholders including the federal government, state governmental agencies, and community-based organizations can improve existing programs and create innovative new strategies to create a hunger-free America.

Braiding and Layering Funding Overview

With the involvement of federal, state, local, and private entities, it can be difficult for state and territorial health departments to obtain funding and develop partnerships with existing organizations and/or agencies who are also working to create a hunger free America. Braiding and layering funding across government and non-governmental funding sources can provide a useful tool in addressing food insecurity. Braiding funding refers to a process in which funds from different sources are either laced together to support a common purpose, retaining its source specific identity. Layering funding refers to funds from different sources are group together, losing their individual identity. Both strategies can be tools to address complex social determinants of health issues, including food insecurity.

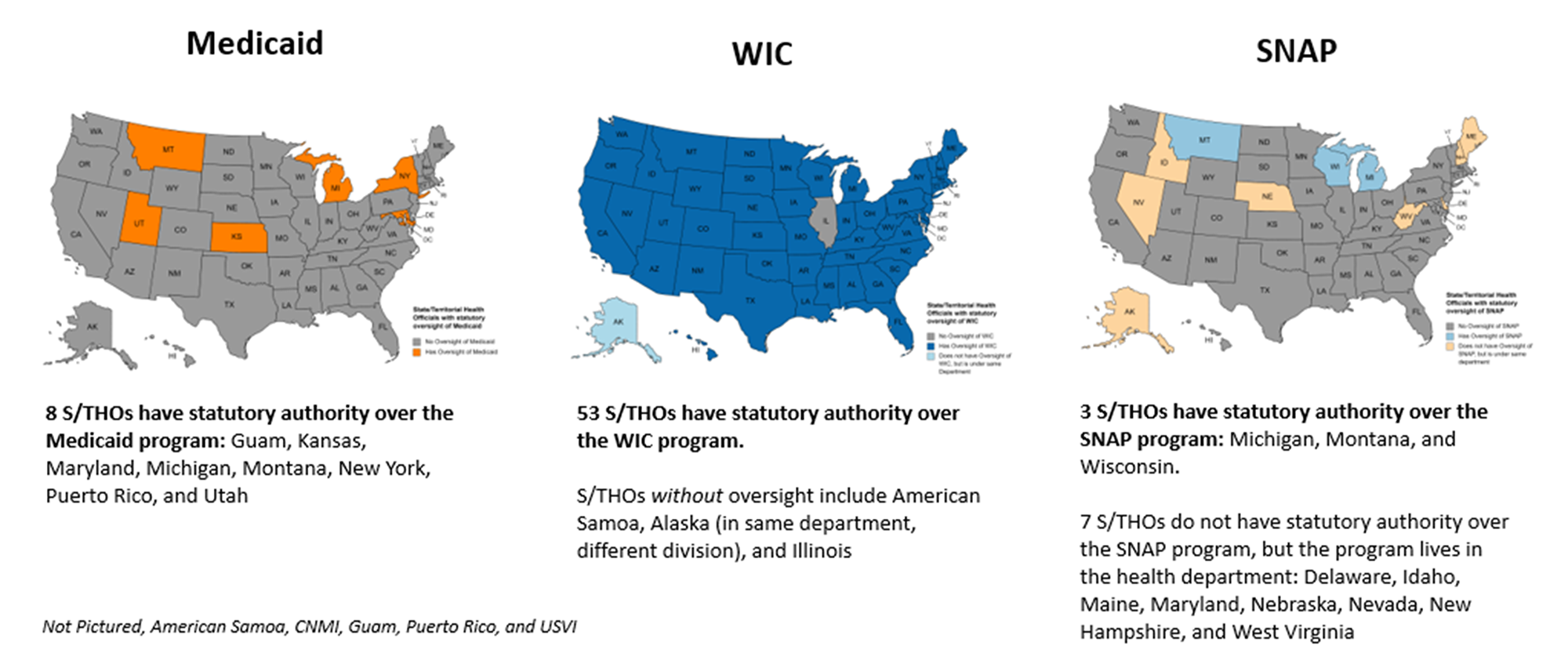

Figure 1: State/Territorial Health Official Oversight of Programs Impacting Food Security

Braiding and Layering: Medicaid

States can pursue Section 1115 Waivers through their Medicaid programs to add specific non-clinical services to their Medicaid benefits package. As noted in the map above, there are limited states with S/THO oversight to the Medicaid program, highlighting the need for robust partnerships and collaboration across state agencies to provide targeted food assistance to the Medicaid population. Pioneering this innovative strategy is North Carolina through its Healthy Opportunities Pilots. Approved by CMS in 2018, the Healthy Opportunities Pilots is the country’s first program to “test and evaluate the impact of providing select evidence-based, non-medical interventions related to housing, food, transportation, and interpersonal safety and toxic stress to high-needs Medicaid enrollees.” CMS approved $650 million in Medicaid funds for the first five years of the pilot program. Within this program, assistance is launched in topical phases, with food and hunger related services being the first implemented on March 15, 2022.

Braiding and Layering: Women, Infants, and Children

In New Hampshire, (Women, Infants, and Children) WIC staff have implemented a widespread outreach strategy to identify and enroll WIC eligible individuals who may face barriers to pursuing this benefit on their own. In 2018, the New Hampshire WIC program entered a data sharing agreement with the state’s SNAP program which allowed the local WIC staff to receive data from SNAP and eligibility files. Through a daily data share only accessible to program staff, local WIC offices create a record for the household and then cross-checks their own files to see if the household is currently enrolled in WIC and if they are eligible to receive WIC services. If the household is not enrolled, WIC staff will then reach out to every cross-referenced household by telephone to assist them in enrolling. While this has been a tedious process for S/THA staff and their local WIC counterparts, the roughly 11% increase in new enrollees and drastically decreased participation drop off rates justifies the more intensive approach.

Given the program’s success, in 2020, the program received a WIC General Infrastructure grant to enhance the project and add Medicaid to the data sharing agreement. Furthermore, New Hampshire used this grant to implement a more intuitive data sharing program that imports all categorically eligible SNAP and Medicaid recipients into the WIC Find Online Application Dashboard and differentiate them from existing applications and recipients. WIC staff then use the same contact strategy as noted above to reach the potential enrollee. This expanded portion of the program was implemented in March 2022 and utilized $106,500 in grant funding.

Braiding and Layering: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

SNAP is an entitlement program which provides monthly benefits to purchase approved food items for eligible populations. While this program is most often run by human or social service agencies, there are a few S/THAs who oversee their programs.

There are also some states, such as Indiana, who have split authority over their various SNAP programs. While the Indiana Department of Health (IDOH) does not oversee SNAP, it does administer a supplemental program called SNAP-Ed. SNAP-Ed grants provide additional funding which allows the overseeing agency to provide additional services around nutrition education and physical health and wellness. While this funding is reliant on an approval of a SNAP-Ed plan, states are not required to contribute or match the federal grant.

In 2018, the IDOH Division of Nutrition and Physical Activity became the overseeing agency of SNAP-Ed, with Purdue University implementing the program. To operate the program, Indiana is estimated to receive $6,880,000 and an additional $4,000,000 million in outside funding. The program provides direct and free education to vulnerable populations and employs community wellness coordinators who act as conduits between state agencies and private partners to address food insecurity within their specific communities.

Despite the pandemic lockdown impacts, in 2021, the program saw success with 93% of adult participants reporting an increase in at least one health supporting activity and the programs community wellness coordinators working on 455 initiatives that reached an approximate 569,000 impacted Indianans.

Conclusion

S/THOs have a variety of strategies and partnerships that can be utilized to address food insecurity within their states and within specific vulnerable communities. Braiding and layering funding can be a powerful tool in addressing inequities and barriers in food access that prevent individuals and communities from reaching their full potential. As record investments in public health come to the state and local levels, S/THOs should continue to assess which strategies can be most impactful in serving their state and communities. To learn more about how these strategies can be seen in action, please refer to ASTHO’s whitepapers on blending and braiding funding to expand access to food and improve proximity to food retailers, which discuss further strategies to increase access and proximity to food.

The development of this product is supported by the Center for State, for State, Tribal, Local, and Territorial Support (CSTLTS) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) through the cooperative agreement CDC-RFA-OT18-1802.