Postpartum Depression: Expanding Screening Practices to Improve Outcomes

September 25, 2020

The United States has the highest maternal mortality rate among high-income countries, in large part due to limited postpartum touch points and inequitable access to quality healthcare. About half of all pregnancy-related deaths occur after delivery, and approximately 12% of these deaths occur from 43 days to one year postpartum; mental health conditions are one of the leading underlying causes of pregnancy-related death. Postpartum depression (PPD) affects one-in-eight U.S. women. According to 2018 CDC data from women in 31 states who delivered a live birth, 20% of women reported not being asked about depression during prenatal visits, and 12.5% of women were not asked during postpartum visits. If undiagnosed and untreated, PPD can severely affect the health and wellbeing of mothers and their children. Access to timely care is vital for improved mental and physical wellbeing for women, infants, and their families. This brief will describe why expanded PPD screening and coverage are necessary for improving outcomes and reducing disparities.

Postpartum Depression Disparities

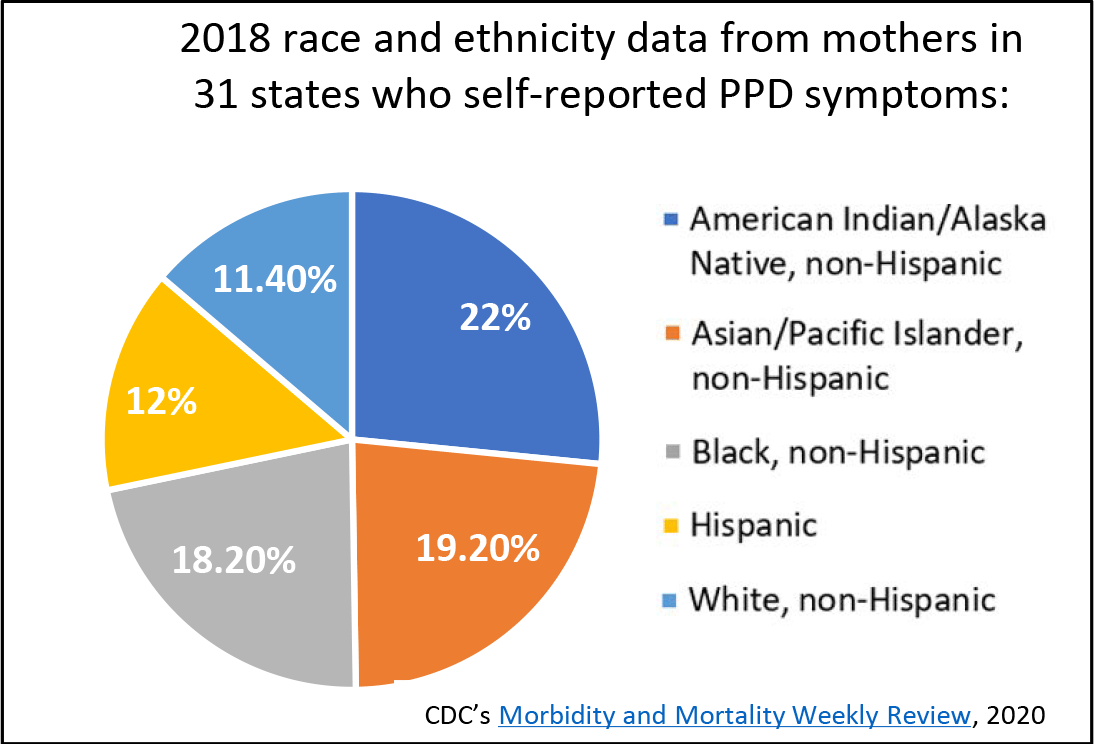

While all women are at risk for PPD, racial and ethnic minority women and those of lower socioeconomic status are at greater risk of not being screened or treated due to systemic barriers and cultural differences. Challenges to equitable access to mental health treatment for women include stigma, racial barriers, perceptions of motherhood, language barriers, immigration status, religion, and cultural sensitivity. As one study reported, women with four socioeconomic risk factors—low income, low education, unmarried, unemployed—were 11 times more likely to experience elevated clinical depression at three months postpartum compared to women with no socioeconomic status risk factors. Even women who perceived themselves as “less well-off” in terms of income, education, and occupation were found to be at a higher risk of developing PPD. Access to screening and treatment for depression are part of the continuum of postpartum care and without it can lead to detrimental and persistent outcomes that negatively impact mom and baby.

Perinatal Depression Screening

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that OB/GYNs screen patients for depression and anxiety at least once during the perinatal period and complete a full screening during the comprehensive postpartum visit. There are several validated screening tools that can help to systematically identify depression. Screenings can happen in different healthcare or non-healthcare settings in order to adapt to an individual’s needs, comfort-level, and circumstances. More Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) clinics and community health centers are beginning to screen with varying degrees of success. Some jurisdictions, like New York City, are utilizing home visiting programs to improve health outcomes, prevent child abuse and neglect, encourage positive parenting, and promote child development. Home visitors in the postpartum period have a unique opportunity to conduct depression screenings in a safe and comfortable environment, and some states are taking innovative approaches to improve competency in this area. State Maternal and Child Health (MCH) programs may choose to utilize some of their Title V MCH Block Grant funding to support and administer depression screening during pregnancy and the postpartum period as well. Several states (Massachusetts, Minnesota, and New Hampshire) highlighted screening efforts in recent state MCH block grant applications and annual reports.

Looking Ahead

State health departments should look to build strong cross-sector programs with providers and systems that expand access to and practice of depression screening. Below are three collaboration strategies to consider.

Provider awareness: Expanding opportunities for culturally appropriate education and training across provider specialties is necessary for early identification and treatment of PPD. While OB/GYNs are the primary access point for pregnant and postpartum women, all provider types, including perinatal nurses and pediatricians, must be appropriately equipped to screen and refer to treatment. Implementing depression screening at well-child visits acknowledges the close relationship between maternal wellbeing and child development and the importance of the mother-baby dyad. The American Academy of Pediatrics’ Bright Futures guidelines recommend depression screening be implemented at the one-, two-, four-, and six-month well-child visits. These guidelines serve as a resource for providers and offer information on which screenings and services should be provided for mothers and infants during visits.

Medicaid coverage: In many states, Medicaid maternity coverage ends at 60 days postpartum, at which point many women lose insurance and continuous access to care. There is no timeline for developing PPD, and if untreated, it can last years with severe outcomes. Recommendations from Maternal Mortality Review Committees (MMRCs) and legislation on the state and federal level have addressed the extension of Medicaid maternity coverage and billable services, particularly for mental health care. In 2016, CMS approved coverage of PPD screenings during well-child visits. Congress introduced the Helping MOMS Act of 2019, which would increase a state’s Medicaid Federal Medical Assistance Percentages during the first year the state chooses to provide continuous coverage up to one year postpartum. On the state level, California passed a bill in Oct. 2019 extending Medicaid coverage up to one year postpartum to cover mental health services.

Continuum of care: A continuum of care and support is necessary to maximize positive health outcomes for pregnant and postpartum women. Depression screenings are only effective when followed up with referrals, so healthcare providers and systems should ensure proper follow-up for diagnosis and treatment. Programs such as Massachusetts’ MCPAP for Moms have built networks of obstetric, pediatric, family medicine, and psychiatric providers as well as dedicated counselors to serve as a community of resources for women, families, and healthcare providers. The Screening and Treatment for Maternal Depression and Related Behavioral Disorders program supports seven state health departments to offer real-time tele-psychiatric consultation, care coordination support, and training to front-line maternity care providers in specified regions, including in rural and underserved areas. Clinical practices might consider embedding mental health providers into their workforce to reduce the need for patients to schedule additional appointments at different clinics. Continuation of care can also be aided by resource mapping, warm handoffs, and expanded training for all providers who interact with pregnant and postpartum women.