Who Is Onesimus?

February 15, 2022 | Kimberlee Wyche Etheridge

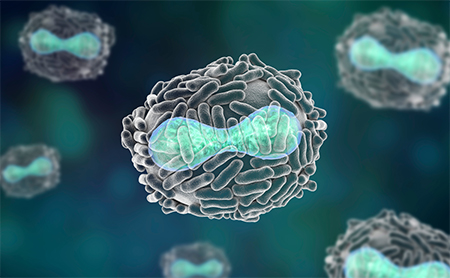

An enslaved African, Onesimus helped to save hundreds of Bostonians from smallpox in 1721. Left out of the history books, he taught others about the practice of inoculation, which was common in Africa and Asia long before vaccines were established. He explained that taking the pus from an infected individual’s pustule and inserting it into the broken skin of a healthy person, led to that person being immune from future infections—a true public health breakthrough in containing a ravenous infectious disease. Cotton Mather, Onesimus’s enslaver, and Zabdiel Boylston, a physician, got the credit and have been cited in history as bringing the lifesaving technique to the American colonies. We have come a long way with immunizations. Now universal in the United States, all children regardless of their family’s ability to pay, have access to the lifesaving shots that are based on this little-known historical figure, Onesimus.

An enslaved African, Onesimus helped to save hundreds of Bostonians from smallpox in 1721. Left out of the history books, he taught others about the practice of inoculation, which was common in Africa and Asia long before vaccines were established. He explained that taking the pus from an infected individual’s pustule and inserting it into the broken skin of a healthy person, led to that person being immune from future infections—a true public health breakthrough in containing a ravenous infectious disease. Cotton Mather, Onesimus’s enslaver, and Zabdiel Boylston, a physician, got the credit and have been cited in history as bringing the lifesaving technique to the American colonies. We have come a long way with immunizations. Now universal in the United States, all children regardless of their family’s ability to pay, have access to the lifesaving shots that are based on this little-known historical figure, Onesimus.

Why dedicate a month to Black history? As strings in the fabric of the country’s soul, this history is part of all of us. History is a puzzle. The final picture only makes sense if you have all the pieces in place. With only some pieces, the final work of art is left to interpretation, which often falls victim to intentional and unintentional biases that usually benefit the orator. The contributions of African Americans, some doctors, scientists, public health officials, and others have changed the way we practice medicine and healthcare for more than 400 years. Because of barriers like structural racism, implicit bias, and theories of intelligence, many U.S. history classes do not mention these pioneers, and without a concerted effort, their names and contributions are lost.

Does the name James McCune Smith (1813-1865) ring a bell? He was the first Black American to receive a medical degree. His journey to medicine took him to Glasgow because local medical schools did not want to admit African American students. He strived to be a physician to help care for communities like those where he grew up, which often did not have access to equitable health care. He has many firsts in his accomplishments, including the first Black physician to be published in a national medical journal, first to own and operate a pharmacy in the U.S., and equally important, he was a pioneer for calling out and challenging shoddy science, including many of the racist assumptions about African Americans. Although it is nearly two centuries later, and we have not achieved race-neutral health care, Dr. McCune Smith set the groundwork that achieving wellness should be an equal opportunity endeavor.

The year before Dr. McCune Smith died, Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler (1831-1895) became the first Black woman in the U.S. to receive a medical degree. She spent much of her career practicing under the pretense that formally enslaved people also deserved to have the chance to be healthy. She worked with the Freedmen’s Bureau in Virginia, and later returned to Boston to treat children in her home, where neither race nor privilege limited access to care. She wrote one of the first books geared towards women and mothers of all races and privilege to provide guide to caring for children.

What about Dr. Charles Drew (1904-1950)? Many know his research was responsible for the establishment of the first national blood bank. Imagine a time when a blood transfusion after a critical accident or surgery was not available. Few know, however, that he dedicated much of his surgery career to changing the American Red Cross’s policy of segregating blood by race. His legacy can be found in the many surgeons and medical students his work has benefitted and inspired at Howard University Hospital, and others across the country. More recently, Dr. Marilyn Gaston was the first Black women physician to direct HRSA’s Bureau of Primary Health Care. Her research showed the benefit of screening for sickle cell disease at birth, which was later added to the Neonatal Metabolic Screening blood test recommended for all newborns.

There are hundreds more throughout history whose names are not taught, whose accomplishments not known. One month out of the year is never enough, however until a time when our country’s history embraces all the truths and celebrates all those who contributed to get us to where we are now, we take February to highlight these African American individuals. Happy Black History Month. A celebration for all to take time and to be intentional about learning and changing HIStory into OUR collective story.