Building an Island Health Equity Framework for the Future

April 21, 2023 | Julia Von Alexander, Karl Ensign

The U.S. island areas are bathed in unique historical, cultural, and geographical contexts. These island communities have weathered centuries of military and outside political impositions, building an identity and strength on their shared culture and values.

So, as ASTHO set out last year to do the important work of developing a health equity framework for the island areas, it was essential that we kept this identity at the forefront of our minds. To this end, we worked hand-in-hand with our island members to ensure that the framework we developed reflected the lived reality of these communities.

The goal of this framework is to outline an approach to advancing health equity and human rights in the island areas in a way that resonates with the cultures and experiences of those who lived there. Once complete, the framework will help guide ASTHO’s work in the island areas.

Today, as we unveil the first iterations of this framework, we are pulling back the curtain on the many conversations and considerations that went into developing this framework.

Framing the Framework

As ASTHO sat down with our island members to discuss what a health equity framework would mean for the island areas, we set the stage for the conversation by considering some existing frameworks. From the World Health Organization to the Bay Area Regional Health Inequities Initiative to ASTHO’s own health equity definition, there was certainly no shortage of existing resources to pull from.

However, it became quickly apparent that these frameworks—carefully crafted to meet the precise needs of health agencies in the continental United States—often fell flat in context of the island jurisdictions. In some instances, these frameworks assumed an availability or proximity of resources and expertise that many of the island areas lack. In other instances, the frameworks failed to acknowledge and make the most of the unique strengths of the island areas. Language, geography, schooling, funding, community outreach, settlement patterns—these were just a few of the unique factors that our island-centered framework would have to address differently.

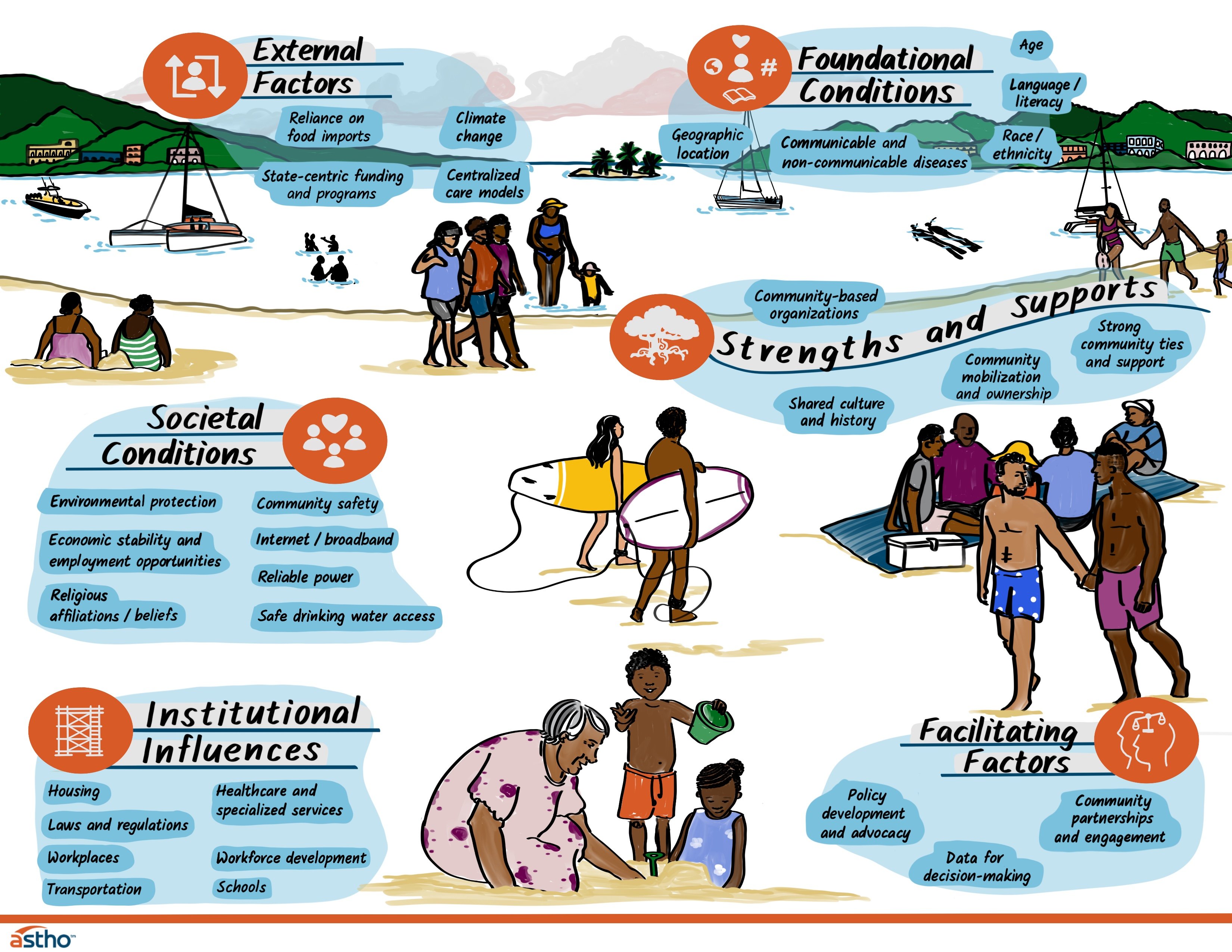

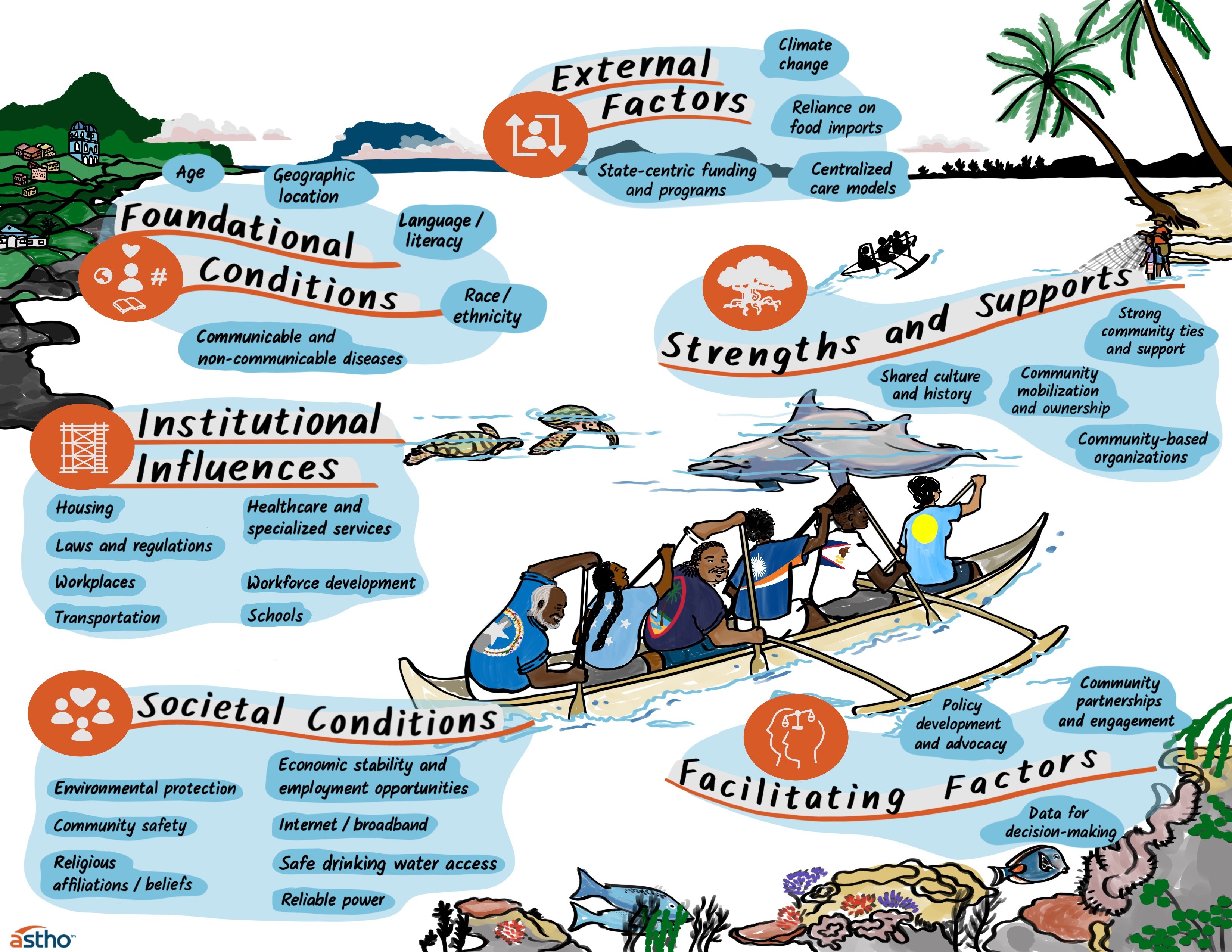

The starting point of this framework—visualized in the graphics below—builds on and recontextualizes current health equity frameworks to reflect the culture, experiences, and strengths of island communities more authentically. To get it right, ASTHO plunged into an iterative process and months-long dialogue with our island members to understand some of the core differences between health equity work in the continental United States and the island areas.

Note: These graphics are designed to help members, partners, and organizations easily identify opportunities for health equity advancement in the island areas. These visuals do not reflect an exhaustive list of factors that can influence health equity or their categories.

Differences in geography are obvious, but often overlooked

One of the more self-evident—but understated—differences between the island areas and continental United States is the stark differences in geography. Puerto Rico—the closest island area to the continental United States—is still over 1,000 miles away. Naturally, this distance has repercussions for the island areas’ imports, service delivery, and program availability. What’s more, following centuries of colonialism, the island areas have become increasingly reliant on imported foods as they drifted away from more sustainable options such as farming and fishery. This has limited their fresh produce and negatively impacted diets.

Island communities are dispersed

Each island jurisdiction includes multiple islands, and their residents live throughout these islands. In the U.S. Virgin Islands, some services must be duplicated across islands. In the Pacific, providing services is especially difficult since there are communities that live in extremely isolated atolls with little infrastructure. Some islands and atolls require a weeklong trip by boat or very expensive chartered flight to reach them. Thus, providing services to all residents in the island areas requires additional staff, time, and supplies.

On-island care isn’t always sufficient

An offshoot to the geographical barrier is the challenge of ensuring that healthcare and specialized services are readily available. In many instances, there is limited access to medical equipment, diagnostic testing, and trained public health staff, requiring people to seek care off-island. Further complicating this matter is that there are often limited flights off-island, making care more expensive and disincentivizing people from seeking the help they need.

Climate change looms large

No corner of the world is exempt from the sweeping ramifications of climate change. An issue that will continue to grow in prominence and importance as it affects water availability and our ability to grow food, we must consider climate change as we plan for the future. In the island areas, the increasing number and intensity of natural disasters—such as typhoons and hurricanes—paired with an already fragile infrastructure has resulted in loss of water, electricity, and health services, leading to higher rates of homelessness, exposure to illnesses, and hospitalization. Therefore, an island-specific health equity framework must highlight climate change as a potentially devastating public health threat to consider now.

How Have the Islands Responded?

With these unique considerations—among countless others—in mind, ASTHO and our island area partners got to work building out a recontextualized framework that mitigated these barriers. This meant not only creating new value for the island communities, but taking advantage of the strengths and value that are a strong foundation in these vibrant communities.

Throughout our conversations about the framework, several opportunities to enhance health equity emerged.

Use data to tell a story

Data can serve as an invaluable decision-making tool for public health experts as they apply for grants and allocate resources. Unfortunately for many of the island areas, comprehensive population health data can be scattered. However, that doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. Puerto Rico is working with community-based organizations—including outside the public health space—to pull together data and build profiles of communities. ASTHO has also been at work supporting our island members in developing data dashboards, and working closely with our members to ensure there is infrastructure (e.g., software licenses) for island areas to develop and maintain their own data dashboards.

Build and earn trust

Many island communities value the faith and spiritual communities they find in their faith-based organizations, their culture, tradition, and family. Family support is an important strength and oral traditions help to tell the story of their past and present, sharing important data and information. Language is also important within the Island Areas as they frequently host migrants from other islands and countries who speak a different primary language. Thus, meeting communities where they are and speaking their language is essential. Guam undertook a community COVID-19 assessment where they focused outreach on “harder to reach” communities and hired assessors who spoke the languages of these communities. This led to a better understanding of what these communities face throughout COVID-19 and how to better support them.

Lean on existing networks of trust

Public health frameworks in the continental United States often assume the presence of a centralized agency, or a kind of “health nucleus,” that serves the surrounding community. However, the island areas’ model of care is typically far more collectivist, with families and communities acting as mutual sources of support and care. Recognizing this as a natural source of strength, experts have recruited people from underrepresented populations to translate and ensure messaging is culturally appropriate, while leaning on community leaders and peer-to-peer support to build a foundation of trust. In the last nine months alone, both Palau and the U.S. Virgin Islands have announced new cohorts of community health workers to improve on-island care and limit the need for inter-island travel. Meanwhile, the Puerto Rico Department of Health is contracting with community-based organizations they haven’t been able to work with previously.

Use funds effectively—and creatively

Braiding and layering refers to the practice of using multiple funding sources in a coordinated fashion to achieve a common goal or outcome. The island areas’ limited funding streams means that braiding and layering funds has an untapped potential in these jurisdictions. The Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, for instance, deftly used a braiding and layering approach to great success to streamline a community-centered non-communicable disease service You can read more from ASTHO staff in the Journal of Public Health Management and Practice and our blog post on using braiding and layering funding to address food insecurity.

What Now?

ASTHO continues to provide technical assistance to the island areas, including by offering workshop series, coaching, guidance documents, peer to peer connections, and tools. Our work has focused on building our island members’ capacity in many areas spanning from building out data dashboards to providing community health worker accreditation to launching new mobile clinics.

No framework can hope to fully plumb the depths of the island areas’ storied pasts. However, ASTHO believes that in partnering so closely with our island members, we have developed a framework that tells an honest and accurate story of these communities’ lives.

We have developed this framework with the caveat that such a framework can never be truly final. It is living, breathing set of goals and priorities that must continue to be responsive to and reflective of the lived realities of the island areas’ residents. We look forward to maintaining relationships with and learning from our island members and the communities they serve.

ASTHO has eight members from the territories and freely associated states, jurisdictions collectively referred to as island areas. Sharing Island Stories on Health Equity is a series of blog posts based on conversations held at the Atlantic and Pacific COVID-19 Health Equity Action Institutes in spring of 2022. Although implicit in our work with jurisdictions, these convenings were the first time ASTHO’s island area members were centered in a conversation about health equity, marking a historic moment for ASTHO’s relationship with its island members.

This product was supported by funds made available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for STLT Public Health Infrastructure and Workforce, through cooperative agreement OT18-1802, Strengthening Public Health Systems and Services Through National Partnerships to Improve and Protect the Nation’s Health award # 6 NU38OT000317-04-01 CFDA 93.421. Its contents are solely the responsibility of ASTHO and do not necessarily represent the official views of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.